This post is going to get a little bit math heavy toward the middle. Just warning you now.

The idea for this post stemmed from a recent discussion on the Star Frontiers: Alive and Well Facebook group talking about the accelerations involved in faster than light (FTL) travel in that game. I’ve written about this many times over the years on forum posts but since I can’t seem to find those posts (I think some of them at least are on the now defunct forums at starfrontiers.org), I’m going to do it one more time here on this blog as a permanent reference. But before I dig into the details of the math and physics, I’m going to share some links to other posts I’ve made that I do still have.

Other Posts

First up we have a post from 2010 on Void Jumping on my Star Frontiers Network site. I don’t think this article is linked from anywhere anymore so this will help to bring it back to life. This essay talks about some of the issues associated with making a Star Frontiers style void jump for FTL travel. This essay was the basis for the sci-fi novel, Discovery, that I published back in 2011 (has it really been that long!).

Next, in 2015, when I was still writing on the Arcane Game Lore blog, I did a series of posts on Void travel that expanded and refined those ideas a little more in the direction of a personal sci-fi game I work on off and on. The first two of these posts were actually part of the November 2015 RPG Blog carnival.

- The first is an article on Void Travel Sickness. Not really relevant to this discussion but fun none-the-less and falls under the “nuggets” heading.

- The second, Your Final Destination – Exiting a Void Jump, talks about variations in your arrival at your destination. The blog carnival topic that month was “Surprises” and both of these articles were things that could add surprises or randomness to your FTL travel. I actually recommend you read this one after the next one as it talks about things at the end of the journey but it can be read first.

- The third (and final) article in that set was part of my “Designing out Loud” series of articles where I talked about game design decisions and ideas. This one was entitled “Designing Out Loud – Void Jumping” and expanded on the ideas in my 2010 article.

While you don’t necessarily need to read those article to follow along with the following, it definitely wouldn’t hurt.

Void Jumping

The concept of the Void Jump was introduced with the Knight Hawks supplement in Star Frontiers. In the original rules (renamed to Alpha Dawn when the Knight Hawks rules came out), there were no spaceship rules and it just said to treat interstellar travel at the rate of 1 light year per day.

So how does it work? According to the rules, you make a jump by leaving your starting point and accelerating until you reach 1% the speed of light. At that point you “jump” into the Void. To get out of the Void, you just have to slow down slightly. While you’re in the Void, you travel amazingly fast, on the order of 1 light year per second (The rules don’t actually so but imply something close to that so that’s the value I use). Once you jump into your destination system, you swing the ship around and start decelerating. Remember, there is no artificial gravity in Star Frontiers so this acceleration and deceleration is what provides gravity in the ships. Most ships make these trips accelerating at 1g.

So how long does this take? For these calculations, we’ll take 1 g to be equal to 10 meters per second squared (m/s/s) of acceleration. On Earth we define 1 g to be 9.82 m/s/s but rounding up to 10 just makes everything easier and its less than a 2% difference.

Okay, here comes the math.

If you start at rest, your velocity at any given time is just:

where v is velocity (in m/s), a is acceleration (in m/s/s), and t is time (in seconds). Technically v and a are vectors but we’ll just worry about speed, not direction.

Now, the void jump occurs at 1% the speed of light. We’ll take the speed of light to be 300,000,000 m/s. It’s really 299,792,458 m/s but we’ll again round up to make the math easier. The difference is less than 0.07%. Good enough for this discussion. 1% of that is just 3,000,000 m/s. That’s our target velocity.

Since our acceleration is 10 m/s/s, dividing 3,000,000 m/s by 10 m/s/s gives us 300,000 s of acceleration needed to reach jump speed. That works out to 83 hours and 20 minutes of acceleration. Given that a standard day in Star Frontiers is 20 hours long, that is 4.17 days.

That’s the time to get up to jump speed. It takes that much time to slow down on the other side as well. Which means at a minimum, an interstellar jump takes 8 and 1/3 days, assuming everything lines up perfectly (see the Exiting the Void Jump article for things that might lengthen that).

That’s the time required. What about distances covered? The equation for position is just the integral of the velocity equation above. Again, for starting at rest, and assuming that you measure the distance from your starting point, your position at any given time is given by:

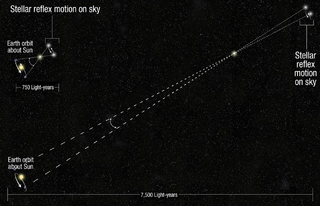

where x is your position in meters. We know what t is from the velocity equation above is 300,000 s. a is just 10 m/s/s. Plugging these in gives us a distance traveled of 450 billion meters or 450 million kilometers. (A lot of people forget that factor of a half and end up with the wrong number.) Now the distance from the Earth to the Sun, called an Astronomical Unit (AU), is 150 million kilometers (again I’m rounding, the actual value is 149,597,871 km so the rounding is less than 0.3%).

So in those 4.17 days of acceleration, you traveled 3 AU. If you started at Earth and headed straight out from the sun, you’d be 4 AU from the Sun. That’s most of the way from Earth’s orbit to Jupiter’s orbit (at a distance of 5.2 AU from the Sun). That distance puts you well beyond the main asteroid belt which ends at 3.3 AU.

Now, these numbers all change if you use a different acceleration. Doing those calculations is left as an exercise for the reader.

ADF and the Board Game Rules

The above all works just fine. The problem comes when you start looking at the rules for the spaceship combat board game and try to rationalize those rules with the math above.

From the board game, we have that one hex is 10,000 km and one turn in the game is 10 minutes of time. Added to that is the ship’s statistic, the Acceleration/Deceleration Factor (ADF) which is described as the number of hexes that a ship can speed up or slow down in a given turn. The fastest ships (fighters and assault scouts) have and ADF of 5.

Let’s look at some numbers. First, what is Void jump speed on the game map. Well, jump speed is 3,000,000 m/s or 3,000 km/s. Since a turn is 10 minutes or 600 seconds, that works out to 1,800,000 km/turn. Given that a hex is 10,000 km across, that works out to a speed of 180 hexes per turn. Since the game map is only 54 hexes wide, you’ll never get to that speed in the game.

The problem comes when people start looking at ADF as acceleration in gees, i.e. that 1 ADF = 1g of acceleration. If you make that assumption, then accelerating at 1 ADF per turn, it would take you 180 turns to get to jump speed from rest. 180 turns at 10 minutes per turn means that it would take just 1,800 minutes, or 30 hours, significantly faster than the 83.33 hours calculated above. Obviously 1 ADF cannot equal 1 g.

So let’s work that out. 1 ADF represents a change of velocity of 10,000 km per 10 minutes in 10 minutes (or 100 km/min/min). That’s an acceleration, just not in the normal units of m/s/s. So lets convert them:

So we see that 1 ADF is really 2.78 g of acceleration. You’re not going to sustain that for 30 hours and have anyone in any sort of condition to function unless severe precautions are taken. Heck, even sustaining that for 1 turn (10 minutes) is going to be rough. It’s doable, that amount of acceleration and duration is roughly equivalent of a launch to low Earth orbit with modern rockets, but you wouldn’t want to keep it up for a long time.

That also raises another issue. 5 ADF is actually 13.89 g of acceleration. And Star Frontiers doesn’t have any sort of artificial gravity tech. Pulling those kind of maneuvers is a little unrealistic. (There are discussions about using interia screen tech to help with this but that’s a different article.)

There are a couple of solutions to this. One, which is the one I use and which is probably the simplest, is a willing suspension of disbelief. The board game rules are just that, rules for a board game that simulates (sort of) spaceship combat. There are other issues with the board game physics besides this one, so I don’t expect it to represent “reality”. It’s a fun way to approximately simulate spaceship combat.

Another option, which immediately removes the 1 ADF not equaling 1 g issues, is to change the size of the hexes in the board game. Simply saying that they are 3,600 km in size instead of 10,000 km, makes 1 ADF = 1 g. If you keep the range of weapons the same (measured in hexes as they are described in the game rules, the only thing that really changes is that any planet counters you put on the map have to take up 7 hexes instead of just 1. And it might tweak the gravity rules a bit, but not significantly. This doesn’t solve some of the other problems, however. That’s a whole different post as well.

How I Apply This In Game

So how do I use this?

Basic Application

For most ships, I assume that they have two astrogators that can work in alternating shifts around the clock to do jump calculations. Since the rules say it takes 10 hours of calculation per light year traveled. And since it takes over 80 hours of travel time to get to jump speed. This means that any jump of 8 light years or less takes the same amount of time, namely 8.5 days, which I typically round up to 9 for maneuvering around the station and slight variations in arrival location (see my linked posts). And actually, since I round this up to 9 days, it play it that jumps of 9 light years or less all take 9 days, regardless of distance. Each light year beyond 9 adds a half of day of travel time to allow for the calculations. This is how I calculate the travel times for ships in my Detailed Frontier Timeline.

Again that assumes that they have two astrogators. If not, jumps take significantly longer, namely one day per light year traveled, plus 4.5 days to slow down at the destination, with a minimum of 9 days total travel. So in this case, jumps of five light years or less take 9 days, and each additionally light year adds a day on to the jump time.

Now I do allow the jump calculations to be started before the ship leaves it’s berth, assuming the crew knows when they plan to leave (to within a day or so). But because the planets and stars are always in motion, and the jump calculations have to be done for each specific jump, no more than half the calculations can be done in advance. The rest must be done “in flight.” For me this represents the tweaking and refining of the ship’s course in preparing for the jump that I discuss in the other articles I linked. But that means that even for a ship with a single astrogator, they can reduce the flight time if the astrogator gets started before they leave on the longer jumps.

Traversing multiple systems in a single trip

Another aspect of this is what I like to call the “high speed transit.” This occurs when the ship wants to traverse several star systems but doesn’t need to stop in each one. In this case, the first jump starts as usual, but once they traverse the Void the first time things change.

In each system after the first, until they reach the final system that they want to stop in, they don’t decelerate, at least not appreciably. But rather remain near jump speed, either drifting or, if they want gravity, decelerating for a few hours, flipping around and accelerating, and repeating until they are ready to jump. During this time the astrogators work on the jump and the engineers do any needed engine overhauls. The amount of time spent in system is just the longest of those two activities. Once that’s done, they nudge into the next system and repeat until they arrive at the destination system where it then takes 4.5 days to slow down.

Let’s look at an example: The UPFS Stiletto, an assault scout, is on patrol in Truane’s Star and has orders to get to Dramune as quickly as possible. This route has 4 jumps:

- Truane’s Star to Dixon’s Star – 5 light years

- Dixon’s Star to Prenglar – 5 light years

- Prenglar to Cassidine – 7 light years

- Cassidine to Dramune – 4 light years

Using normal jumps, these are all less than 9 light years so each jump would take 9 days for a total of 36 days.

Rather than do this, let’s look at what this takes using the high speed transit option. According to the rules, engine overhauls take 60 hours minus 1d10 hours for each engineer level. The rules also say that Spacefleet ships typically have level 4 engineers. That means that on average, it will take 38 hours to overhaul each engine. We’ll assume that there are 2 astrogators and 2 engineers onboard the Stiletto. This is what a high speed transit looks like in this scenario:

- Accelerate out from Truane’s Star – 4.5 days – plenty of time to do the 50 hours astrogation calculations

- Transit Dixon’s Star – astrogation calculations take 50 hours (2.5 days of round-the-clock work), engine overhauls only take 38 hours of work, but since there is only one engineer per engine, they have to sleep. So these are the slow part, taking 4 days – so after 4 days, they jump to Prenglar

- Transit Prenglar – astrogation will take 70 hours (3.5 days of round-the-clock work). This one is closer but the 4 days of engine overhauls is still the limiting factor. After 4 days they jump to Cassidine.

- Transit Cassidine – Here the astrogation calculations only take 40 hours (2 days of round-the-clock work) and the astrogators get a bit of a break while the engineers finish up. After 4 days, they make the jump to Dramune

- Decelerate in Dramune – it takes 4.5 days to slow down and arrive at Inner Reach.

All told, this trip takes only 21 days instead of the baseline 36, saving 15 days of travel. The crew might be a little tired, but they made it without taking any risks.

If you only had 1 astrogator and two engineers, one level 3 and one level 2 (more likely on a merchant ship or PC ship), the transit looks like this:

- Accelerate from Truane’s Star – 4.5 days, same as before. We assume the astrogator got started before they left.

- Transit Dixon’s Star – Astrogation takes 5 days, engine overhauls take 43.5 for the level 3 engineer and 49 for the level 2 engineer. The level 3 engineer can help the other engineer once they are done so the total time to do the overhauls is five days – Time in system 5 days.

- Transit Prenglar – In this case the limit is the astrogation which takes 7 days. Time in system, 7 days.

- Transit Cassidine – This time the astrogators win and the jump is waiting on the engineers – Time in system, 5 days.

- Decelerate in Dramune – 4.5 days.

Total time: 26 days. Takes a little longer but still faster than the base 36 hours. If there was only one engineer, it would actually take longer than 9 days per system as one engineer just can’t do engine overhauls on two engines in each system that fast (unless they are level 5 or 6). You might as well stop over in the station each time unless you have a reason not to go into a system.

Final Thoughts

That’s it for this post. There are other aspects of the travel that I could talk about such as vector movement, the process of lining up for a jump, what happens to your calculations and alignment when you have to maneuver for a combat or something else, and a discussion on how long those alignment efforts take anyway. Some of those ideas I touched on in the posts I linked. I might look at these again in a future post or two as well.

What are your thoughts? What questions do you have? Share them in the comment section below.