Last week we looked a bit at the logistics of running a passenger transport system between the various worlds and saw that if you wanted daily flights between all the worlds, you’d need over 600 ships. And that would only give you 250 people moving between each world each day.

Now you can change that a bit by making the ships a bit larger or increase the passenger density. But it gave us a feel of what assumptions or changes you need to make to your setting if you want a certain level of interaction between the worlds. Or if you limit the number of ships and passengers, some ideas of what impacts that has on the culture and setting.

In this article, I am going to look at the financial side of the passenger transport business. We’ll start by actually designing our starliner to get an idea of costs and expenses, look at ticket prices, and decided if it is even worth it. Then we can talk a bit about other changes that we need to make, if any, to make this all make sense. Let’s get started. You might want to settle in. This one is a bit long.

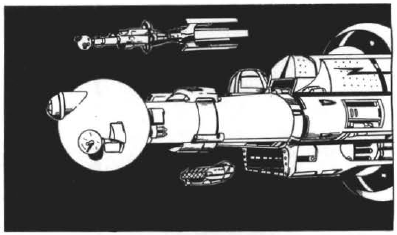

Our Ship

If we’re going to look at economics, we’re going to need details on the ship. In the last article, I based everything on a HS 10 starliner. We’ll detail that ship out and look at its cost.

Hull and Engines

As a HS 10 ship, it will have three engines, which from the discussion last week, are atomic. I realize now that as a passenger liner, maybe we don’t need the power of the atomic engines and can get by with ion engines. Surprisingly, in the discussion that the previous post generated, no one mentioned that. It would also save on the overhaul time as ion engines don’t need that so the ship could be turned around in port more quickly. But for now, we’ll stick with the atomic engines.

Cabins

The next major question is how many of the various passenger berths we have of each class. We have a total of 250 berths. Journey class are the standard. Interestingly, the only safety requirement listed in the rules is that a spacesuit has to be provided. You don’t actually have to have lifeboats for everyone. First class berths are more expensive and require more cabin space, cargo space, and facilities for the passengers. And do need access to a lifeboat. Storage class cabins are cheaper for the passenger and have minimal storage space, but are more expensive to install in the ship, costing as much as a First Class cabin. With the standard starship construction rules, these tradeoffs really don’t affect the design of the ship other than the final cost as the system doesn’t really account for the space and facilities needed. So for this analysis, I’m going to roughly base these ships on our modern airlines, with most of the cabins of the base Journey Class category with a few First Class and some Storage Class. The breakdown will be 40 First class, 180 Journey Class, and 30 Storage Class.

Crew

The other major decision is the size of the crew. We will need to purchase cabins and life support for them as well. The rules give no guidance on this. Looking at cruise ships, it is about a 1-to-5 ratio, crew to passengers. Some of that, such as janitorial and maintenance work, will get automated away to robots on our star liner, but then we’ll need people to look after the robots as well. We’ll design the ship around a crew of 50. We’ll talk about the breakdown later when we have to figure out what they are paid.

Ship Vehicles

While we only need lifeboats for the First Class passengers, we’re going to have lifeboats for all of the passengers (except Storage Class, that’s just one of the hazards of the cheap fare, you are frozen and can’t get to a lifeboat) and the crew. And we will toss in 10 escape pods so not everyone has to make it to a lifeboat. As the final vehicles, we’ll add in 5 large (10 being) launches for shuttling people around between the station and ship, 2 small (4 being) launches for the crew’s use, and 2 workpods for ship maintenance.

Spacesuits

We are required to have spacesuits for all of our non-Storage Class passengers. Plus we’ll have them for the crew as well. Technically, each species has its own style of spacesuits adapted to their physiology. The rules, however, only distinguish between vrusk and non-vrusk as they are only really concerned with cost and the standard spacesuit is 1000 cr. while the vrusk suit is 1,500 as they require more material. If we assume that vrusk make up one quarter of the crew and passengers, and we build in a bit of buffer in the numbers to account for varying numbers of the different species, we’ll get 80 vrusk spacesuits and 220 non-vrusk ones. This is 300 total, which is exactly our crew and passenger count but remember that the 30 Storage Class passengers won’t be using one so we actually have 30 extra.

Robots

There will be a number of robots on board to handle things like cleaning, maintenance, some food production, etc. We’ll design the ship to have 50 robots, basically doubling the crew size. These will be a mix of level 3 and 4 service and maintenance robots, will possibly a small number of security robots. Overall the average cost of each robot will be 4,000 cr.

Other items

There are a number of other items that go into building the starship such as radios, intercoms, computers, portholes, Velcro boots for crew and passengers, toolkits, etc. We’ll add those in as appropriate and list the details in the final stats when presented in the next section:

PGCSS Prenglar Glory

Here are the full KH stats for the ship along with its price tag, fully fueled.

HS: 10

HP: 50

ADF: 3

MR: 3

DCR: 50

Engines: 3 Class B Atomic, 6 fuel pellets each

Sensors: 400 Portholes, radar, camera system, starship astrogation suite

Weapons: None

Defenses: Reflective Hull

Life support capacity: 500 beings, 200 days with full backup

Passenger Accommodations: 40 First Class cabins, 180 Journey Class Cabins, 30 Storage Class cabins

Crew Accommodations: 50 Journey class cabins

Vehicles: 10 escape pods, 14 lifeboats, 2 workpods, 5 large launches, 2 small launches

Computer Level: 4 (175 FP)

Computer Program: Drive 5 (64), Life Support 1 (4), Alarm 3 (4), Computer Lockout 4 (8), Damage Control 3 (8), Astrogation 4 (24), Cameras 1 (1), Robot Management 4 (16), Information Storage 3 (8), Communications 2 (6), Installation Security 3 (12), Computer Security 4 (16), Maintenance 2 (4)

Backup life support computer: Level 1 (4), Programs: Life support 1 (4)

Robots: 50 level 3-4 maintenance, security, and service robots

Other equipment: 220 non-vrusk spacesuits, 80 vrusk spacesuits, 300 velcro boots sets, 5 Engineer’s toolboxes, 10 sets of Magnetic shoes

Cost: 5,658,000 Cr.

The Ship’s Crew

Now that we know the design of the ship, we need to decide on crew makeup. This will determine the wages owed as we operate the ship in the space lanes. This is going to be an approximate mix. The exact details may vary ship to ship but will give us a starting point to figuring out the operating costs when we get to that stage. The crew makeup I settled on, allowing for round-the-clock operations is:

- 2 Pilots – level 5 – necessary to operate a HS 10 vessel

- 2 Astrogators – level 3 – It’s an established route so these could be even lower level

- 2 Engineers – level 4 – as discussed last week for effecting the engine overhauls

- 4 Technicians – level 4 – assistants to the engineers and helping with on-board maintenance

- 4 Roboticists – level 4 – maintain the ship’s robots

- 2 Computer technicians – level 2 – basic computer operations and maintenance

- 10 Safety and Security staff – level 3 (beam) – assisting passengers and keeping everyone in line

- 3 Doctors – level 4 – for maintaining the health of crew and passengers

- 10 Food Services staff – level 3 – cooking, maintaining hydroponics, servers, etc

- 11 other staff – level 2 – any other duties, entertainment, etc.

Now some of those, such as security, food services, and other could slosh around a bit depending on exactly want you want on the ship and what roles all those robots play, but this mix give us a starting point.

The Economics

Okay, with the ship squared away, let’s look at the income and expenses of running this ship.

For this analysis, we will be looking at a single jump. This means that we’ll be covering the 14 days from departure from one station until the ship is ready to depart the other one. The Knight Hawks rules are based around yearly or 40-day “months”. So we’ll often be scaling the values from the rules to cover just the 14 day period.

Let’s dive in.

Income

There is really only one source of income on a starliner, paying passengers. The KH Campaign Book, page 44, covers the operations of a starliner. We’ll start with the Spaceliner Bookings Table.

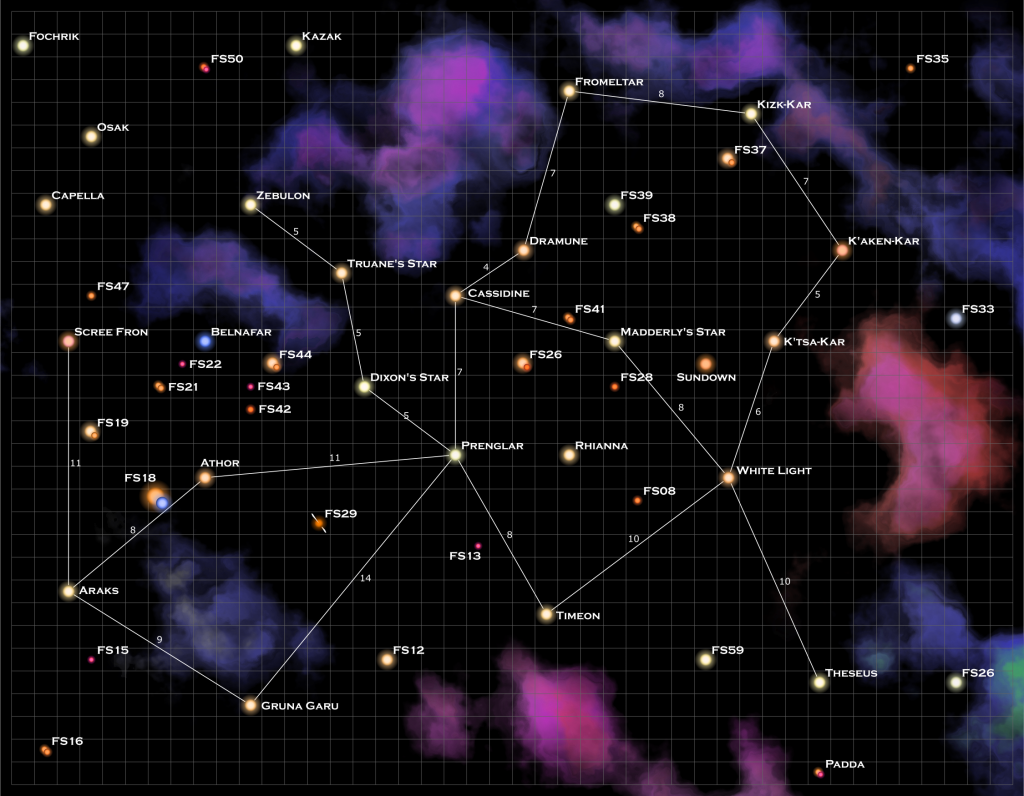

This table tells you how many of your berths a ship will fill traveling between different population worlds. Now to be honest, I believe that this table really represents the situation if there were lots and lots of travel available. If there is only a single ship flying between the two worlds each day, it will probably fill every berth every trip. And depending on the route, it might be higher than that given by the table. For example, traveling from Prenglar (high population) to Dixon’s Star (outpost) gives only a low fill percentage but in truth, most of those people are actually going to Truane’s Star (medium population) and so the ship would be fuller. But I’m going to leave those details as an exercise for you to do for your version of the Frontier. I’m going to take the table at face value here.

This ship is flying between Gran Quivera (Prenglar) and Triad (Cassidine), which are both high population worlds. According to the table the ship will fill 80+2d10 percent of its berths on any give trip. We’ll just deal with the average which is 91%. That means on an average trip we will fill 36 of our 40 First Class cabins, 164 of our 180 Journey Class cabins, and 27 of the 30 Storage Class berths. Sometimes it will be more, sometimes it will be less but that’s the number we’re going to use.

The jump from Prenglar to Cassidine is 7 light years. That means that a First Class ticket costs 1400 cr. A Journey Class ticket costs 700 cr. And a Storage Class ticket costs 210 cr. Given the number of berths being filled, that means that our income for any single jump is 170,870 cr.

That’s our gross ticket sales. We need to fit all of our expenses for a trip into that number. So let’s look at our expenses.

Expenses

First up is fuel. We have three atomic engines and each jump uses a fuel pellet in each engine. Since each fuel pellet costs 10,000 cr., each jump costs us 30,000 cr. in fuel.

The next obvious cost is the crew salaries. Daily wages for characters with spacecraft skills are given on page 54 of the KH Campaign book. Daily wages for characters with AD skills are given on page 60 of the AD Expanded Rules book. For the “other crew” line I just uses 10 cr. x level as their pay rate and for the food services crew I use 10 cr. x level+1. I’ve also ignored the fact that characters may have multiple skills and the pay rate is just based on their primary skill level. With the crew as detailed earlier, the daily cost for the entire crew is 3,690 credits. Which means for the 14 days of our trip, the crew wages come to 51,660 cr.

After those two, the next largest cost is maintenance. The ship has to spend 15-16 days in maintenance each 400-day year at the cost of 1,000 cr. per day. In 400 days, a ship can make 400/14= 28 trips 8 days left over. That means that we can make 27 trips a year. So each trip needs to save away 16000/27 = 593 credits to cover that expense at the end of the year. To be safe, and cover other unexpected maintenance costs, we’ll stash away 1500 cr. each trip.

We’ll also need to pay the crew during those 16 days as well so we need to save away a total of 59040 credits to cover wages. That means each trip needs to save 59040/27 = 2187 credits which we’ll round up to 2200.

Each trip consumes life support. According to the rules, refilling the life support system on the ship costs 15000 credits every 200 days or 75 credits a day. Thus our 14 days of operation use up 1050 credits worth of life support.

Another expense is an office at each end of the line where passengers can come to buy tickets. The rules state that this costs 500 credits per 40 days at each station or 12.5 credits a day. With two end points that’s 25 credits a day or 350 credits of expenses for the 14-day period. We need to squirrel way a bit of funds to cover the 16 days in maintenance but it’s not that much and we can assume it’s covered by the extra maintenance money we saved.

Finally, there are docking fees. Here we are going to use the number given on page 32 of the module SFKH1: The Dramune Run, where it says that the standard rate for docking fees is 2000 credits a month. Assuming that is the 40 day “month” we’ve been using, that works out to 50 credits a day or 250 credits for the 5 days in port during each run.

Tallying that all up, we get that the operating expenses for the ship total 86,810 credits for each leg of our run between Gran Quivera and Triad.

That seems pretty good. We’ve got just over 170,000 credits in income and just under 87,000 in expenses. Which is all well and good if there aren’t any taxes, and if the ship is paid for.

Now the rules don’t explicitly give rates for taxes, tariffs, and other fees associated with interstellar travel although they do talk about varying the rates for wages, docking fees, ticket prices, etc. that can affect the income or expenses for our ship. And in the AD rules, when talking about PC and NPC character wages, it says to assume half of all their income goes towards living expenses and talks about raising/lowering taxes to adjust the amount of money the PCs have. And local governments and the UPF need to get income from somewhere. I’m going to leave the taxes issue up to you for your campaign. But a corporate tax of say 5-10 percent of gross sales might not be unreasonable.

Paying for the ship

But now we come to the biggest expense, at least during the early years of operating the spaceliner. How did we pay for that ship in the first place? Maybe this is a mega-corp and they had a huge budget and could just pay for it outright. They still need to recoup the cost of the ship but at least don’t need to take out a loan. If it’s a smaller organization, they may have to get a loan for the cost of the ship, either in part or in full. Let’s look at those two scenarios. And we’re going to ignore taxes. Subtracting our expenses from our income, that leaves us with 84060 credits after each trip.

First, the mega-corp, paid in full option. Assuming every one of those net credits earned goes into paying back the cost of the ship (which from above is 5,658,000 credits), it would take 68 trips to pay off the value of the ship. At 27 trips a year, that’s two and a half years to recoup the cost of the ship. If there are unexpected costs, it will take longer.

Let’s look at a smaller organization that has to take a loan. Pager 42 of the KH Campaign book gives the monthly payment on a 10,000 credit loan amortized over a number of years from 1 to 20. Now, the game was written in late 70’s to early 80’s and the interest rates back then were high, on the order of 10-15% for low risk ventures. So the interest rates for starship loans, which are considered high risk, are set at 4% every 40 days or, over the 400 day year, an APR of 48%! That may seem a bit high, even by late 70’s standards and especially today, but we’ll go with it as that is what is in the rules. If you want to do the math and come up with a different interest rate for your setting, go for it.

We’ll start by looking at a 10-year loan. Using the table on page 42 and the cost of the ship from above, and assuming we finance the whole thing. The cost of the loan is 230,903 credits every 40 days or 80,816 credits every trip. We had 84060 credits left so that’s good, the net difference is still in the black at 3,244 credits. But we have to account for that 16-day maintenance period where we still have to pay the loan but aren’t making any income. The loan cost for that 16 days is 92,362 credits. Spread over the 27 trips in the year that comes to 3421 credits that need to be saved. Which puts us in the red by 177 credits. Considering we had a bit of buffer in our maintenance budget, to the tune of about 850 credits, we can cover that small deficit from that.

So that means, if we have a 10-year loan for the entire value of the ship, we can just break even if the ship operates continuously and don’t have any problems for a decade. It can be done, but it will be tight. But if we run into unexpected problems, we’re going to be in trouble. We could look at a longer loan, but beyond 10 years, it doesn’t really help. Even a 20-year loan only puts us at 1454 credits in the black each year but takes twice as long to pay off and we end up paying twice as much for the ship.

That’s just to break even, there are no profits beyond the wages for the crew so hopefully the owner is part of the crew or they get no money for the first decade. And that is the economics for a run between two high population worlds were we basically fill the entire ship each trip. On a run with fewer berths sold, there would issues on the scenario where the ship was financed. Also, if there are any taxes, we would really be in trouble. It looks like any fraction of the ship that can be paid for up front will make the operation be more financially stable.

Some Variations

This article gives you a baseline for operating your starliner. I will leave most of the variations up to you but look at one. Some of those variations include, but are not limited to, changing ticket prices, changing the mix of berths, shortening the time in port so you make an extra run or three each year, selling more (or less) of the berths, different crew expenses, and using ion engines instead of atomic engines. I’m just going to briefly look at the variation where we fill the ship completely every trip. Which may very well be the case if there is only a single flight each day between worlds.

In this case, the only real change is that have 13 more paying customers across all three berth classes. That means that our income goes up to 188,300 credits an increase of 17,430 credits. Since our expenses don’t actually depend on the number of passengers (the life support costs probably would, but we ignored that), that is all extra profit. In this case, we are now 17,253 credits in the black after each trip, assuming we keep the 10-year loan.

And that means we either have some profit for the owners and can save a bit for other unexpected expenses, or we can shorten the loan term a little bit. We were right at the bleeding edge as far as the loan went and were already in the point of diminishing returns with respect to lengthening the loan. With a full ship every trip, we could shorten the loan period from 10 years to 5 years and still have a 5,400 credit surplus. And reduce that actual amount we pay for the ship (principal and interest) by 57%, a savings of 9,921,303 credits, which is enough to buy almost 2 more ships! The total cost of the 10-year loan was just over 23 million credits, four times the cost of the ship. That interest rate is very expensive.

Conclusions

So, running a passenger liner between two high population worlds is doable. It might be tight for a few years (up to a decade) if you can’t pay for at least part of the ship up front and have to finance it, but it can be done. Runs between smaller worlds might not be possible using the table from the rules to determine the number of berths filled.

This also gives you as a setting designer some ideas of knobs to turn to tune things in your setting or describe what PCs see as passengers on one of these ships.

What did I miss? What other variations might we look at? Have you ever had PCs try to run a passenger liner? What happened? Share your thoughts in the comments below.